Datsun 240Z: The DEFINITIVE History

Have you ever wondered why automakers build sports cars? Companies dump untold sums into these passion projects and equip them with bleeding-edge technology. With this level of investment, they can’t simply be making them for kicks. So what gives?

If one asked former Nissan president Katsuji Kawamata this question sometime in the 50s, he would have said that they weren’t for making money. To him, they were meant to embody the very best a company could bring to the table. Designers see them as creative outlets while engineers use them as experimental hotbeds. If executed properly, a sports car can earn the respect of industry rivals and elevate a brand in the eyes of the general public. Whatever profits are sacrificed in these endeavors pale in comparison to the prestige a manufacturer stands to gain from them. For a while, the company’s own sports cars reflected this principle.

The 1959 S211 wasn’t a very successful venture, financially speaking. It had a fiberglass body much like the Corvette of the day. While this kept the svelte sportster light on its feet, it also introduced a manufacturing roadblock. Assembly was a slow and laborious process. It’s no wonder why Nissan only managed to build about 20 of them.

They were in it for the long haul, though. Instead of swearing off sports cars, Nissan collected itself and released the redesigned SPL212 in 1960. This featured conventional steel bodywork as well as a more powerful 43-horsepower engine. It proved to be an important part of their American product portfolio. 288 of them were produced between January and October, and most of them were exported to the American market. This made up a considerable part of their US exports that year, which totaled just 1,640.

The Datsun brand fleshed out its lineup in the ensuing years and roadster sales stagnated for a few years. Its direct successor, the SPL213, found its way into just 297 homes during its time on the market. For comparison’s sake, Datsun exported 3,948 cars to the United States between 1961 and 1962.

The redesigned 300-series roadsters were by far the most successful of the line. From 1962 to 1970, US exports totaled 38,557. Datsun exports to the country as a whole, meanwhile, came in at just under 413,000 during that same span. While they weren’t huge moneymakers for Nissan, they were vital to establishing its reputation in the early years. At a touch over $3,000, the 2-liter Sports 2000 was one of the stronger options in its segment. It had a 135 horsepower, 132 lb-ft torque motor as well as a curb weight of 2,100 pounds. These were healthy figures at the time, and they translated to superb real-world performance.

A 1968 Car and Driver test revealed a 0-60 time of 9.3 seconds and a quarter-mile time of 17 seconds flat. That same review told of an unforgettable driving experience. Heavenly engine noises and a buttery-smooth 5-speed manual transmission made it much more than a paper tiger.

This stellar out-of-the-box performance made it popular with enthusiasts. Backyard racers could wring more power out of its engine with ease. It also found success in the higher echelons of competition, bringing home multiple SCCA titles in the late 60s and early 70s. Even though it was a very accessible machine, the Datsun Sports proved to be a very effective halo car for the brand. Few others on the market could match its combination of price, performance, and pedigree. Great as it was, it did have its shortcomings.

Nissan had an unusual setup for its operations in the United States. Soichi Kawazoe was in charge of the eastern part of the country while Yutaka Katayama managed the west coast. Both of them were hearing out negative feedback from Datsun Sports owners. Those near the Atlantic had to contend with atrocious weatherproofing. The canvas top couldn’t keep water out of the interior. One unhappy customer even stated that they could see the sky through the gap between the door sash and the top. Performance in the snow was as equally abysmal.

Inadequate protection from the elements wasn’t as much of a concern out west. Style was at the forefront of their minds, and the folding roof had the potential to spoil an otherwise well-sorted exterior. The Sonoran sunshine drained the color out of them. This issue was so widespread that the design department kept a pile of bleached tops in the corner of the office. It also didn’t integrate very well with the rest of the design. Some dealers likened the supports to the ribs of a hungry dog while Car and Driver referred to it as a “giraffe transporter” with the top up.

No doubt the biggest mark against it was its mass appeal or lack thereof. It doesn’t matter how much power it has or how sharp the handling is. An open-top car will always be a tough sale for the masses. They’re machines of compromise and thus seen as a luxury; objects that many lust after but few can justify.

A closed-body car might’ve very well been their answer. It could be more practical, provide superior practicality, and be more structurally stiff. Best of all, both cars could be produced at the same time since they’d likely appeal to different customer bases. The Datsun Sports could remain in the lineup as an enthusiast’s delight. The unnamed coupe would be there for those wanting a sporting character in a more sensible package. For years, Katayama and Kawagoe begged the product planners in Japan for cars designed with the west in mind. Little did they know, something in that vein was right around the corner.

DESIGN PHASE

Designer Yoshihiko Matsuo has always been a strong-willed person. Back in his youth, his father discouraged him from pursuing a career in design. He felt that the outlook was uncertain and pushed Yoshihiko to work in a more conventional field. Instead of donning a suit and tie, he took the entrance exam for the Tokyo University of the Arts in secret. He failed not once, but twice, though he still didn’t doubt himself. After a slight pivot, he earned a seat at Nihon University.

While in school, he was involved in the development of the three-wheeled Midget. Companies such as Daihatsu and Matsushita Electric tried courting him after he graduated, but in the end, he joined Nissan in 1961. His first assignment here was to design the Datsun Baby for Kodomo no Kuni, an amusement park in Yokohama. It was based on the Cony Guppy and intended to teach children about cars and safe motoring.

He then worked on an update for the Pininfarina-designed 410 Bluebird, which was in a sales slump. Management took note of his efforts when the design department was restructured the following year. It was now comprised of four sections. The first was for mainstream models, the second for large sedans, and the third was for luxury cars. The fourth oversaw sports cars, and the young Matsuo was placed in charge of it.

He didn’t have many resources at his disposal to start. Fellow designer Akio Yoshida was the only other member of the department. There also wasn’t anything in the works at that time. The Datsun Sports was already in the middle of its product cycle and there were no plans to work on any new projects. In a 2017 interview with Jalopnik, Matsuo referred to the promotion as being named “chief by name only.” He could also use the relative seclusion to his advantage. By being in their own section, the designers would have the ability to quickly get their ideas off the ground without yielding to other voices. And boy did they have an idea.

Work on a new sports car began in November of 1965. The process early on was more akin to how a studio would approach a concept vehicle. All manner of ideas were explored, and as a result, the development timeline is a bit scattered. We’ll be primarily focusing on the progression of two threads. Matsuo initially envisioned a lightweight roadster based on a 2-liter 4-cylinder engine. This path is commonly referred to as Type A.

If that sounds familiar to the Datsun Sports 2000, that’s because it is. A 1973 article in Wheels Magazine says that the first proposal was for a roadster that would outright replace it--. While the 2000 has its own identity, it does take after the likes of Triumph and MG. This is most evident in the front-end treatment. It has a prominent grille, pillowy surfacing, and large, upright lamp housings. The blunt nose also ends rather abruptly.

This sketch that Matsuo made in 1965 previews the direction that he had in mind. It’s decidedly more Italian in its execution, with headlight covers, a long hood, and sharper detailing on the whole. The grille also sits lower on the body and is bisected by the bumper guard, which goes from an afterthought to a greater part of the overall design.

This drawing from early 1966 further reinforces the kind of surfacing that they were after. It introduces the prominent power dome on the hood and emphasizes long horizontal lines.

The prospect of a fixed-head coupe was also explored, as evidenced by this sketch from the same year. It should look pretty familiar at this point. Many of the major elements from the previous drawings come together in a softer, more sensual package. Light starts on the hood, flows under the window, and spills onto the shoulders.

The Type A proposal was coming together rather quickly, but management wanted Matsuo to explore a solution that was based on the outgoing Silvia. We’ll refer to this one as Type B. Models in this line are characterized by their boxier, more conservative styling.

A third series emerged in the middle of 1966. Type C cars distinguish themselves from the other lines with their retractable headlamps. While this path was shelved near the end of the year, traces of the greenhouse and pillar treatment would make the jump to the production car.

The aforementioned Wheels article also detailed the unusual way that designers were churning out some of their full-scale models. Clay studies are effective in showing how a car will look in three dimensions, but they are also costly and time-consuming to put together. To maintain their steady supply of models, they turned to some other, less conventional materials. Paper bodies were pulled over wood and wire frames. In addition to allowing them to preview ideas more quickly and cheaply, it also allowed them to ‘pursue an ideal harmony of light, color, and form.”

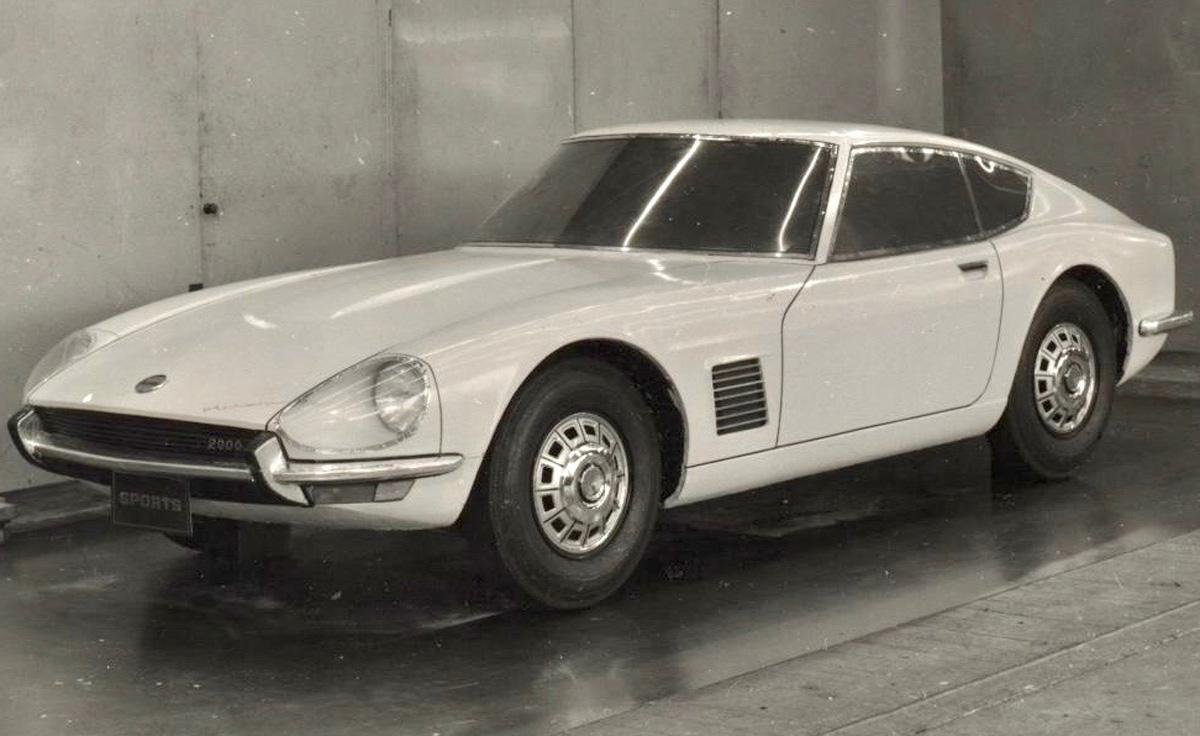

In time, the project gained a bit of focus. The direction previewed in the Type A models became the frontrunner. The A-V model, completed later in 1966, showcases many of the Z hallmarks in one form or another. A low, longitudinal grille is bisected by the bumper guard. The “sugar scoop” light housings come into form as well. Nissan had a great deal of trouble making this part out of metal, so they went with fiberglass-reinforced plastic. Using this method, they were able to easily make the part at a low cost. Nissan switched over to metal in subsequent model years.

The side gills didn’t make it much further than this model, as they presented further manufacturing issues. Other details as well as the overall proportions would be altered as well, but the fundamental building blocks were finally in place.

ENGINEERING PHASE

Chief engineer Hajime Suitsu met with other department leads in April of 1967 with the goal of hashing out a more concrete development timeline. They wanted the project wrapped up by August of 1969. While this is an aggressive deadline, it wasn’t unheard of for a Japanese sports coupe of this vintage. Take the 2000GT for instance. Yamaha inked a deal with Toyota in July of 1965. In August, they finished work on the first prototype. A show car was ready in October and, after going through its paces on the race track, the production model debuted in May of 1967. Nissan could keep to schedule so long as they planned effectively.

They also had two engines in mind for it. The base power plant would be the 1.6-liter 4-cylinder L16 engine. The 2-liter L20 inline-six would be positioned above it. At the time, harsh engine displacement taxes discouraged Japanese automakers from exceeding a displacement of 2 liters. The engineering team briefly considered selling one equipped with the Y40 V8 in the United States, though low demand and assembly line difficulties spelled an end to the idea.

Although it was still too early to nail down the retail price, they did want to target a base figure of about $2,500. At that price point, it was almost dead on with the Sports 1600. They were certainly still envisioning the Z as an outright replacement for that line rather than a companion model. While their plans in this regard would change further along in the process, it does reveal where Nissan wanted to position it in the market.

This was at odds with the wishes of Nissan’s Japanese sales arm, which wanted something that was more on par with the 2000GT. That car was one of the most prestigious machines in Japan at the time. Dealers were probably kicking themselves for relinquishing the spotlight to Toyota. In hindsight, it was probably a wise move on Nissan’s part to try and penetrate the other end of the market with a more accessible product.

Another meeting took place in July. Here, they decided to focus on three body styles. Priority would be given to the coupe while convertible and 2+2 variants would be developed in the background.

Making good on their strict price projections proved to be a serious challenge. They reused parts from other models whenever possible. Hitoshi Uemura, a member of the development team, recalled an exchange he had with one of their suppliers during an earlier project. The front suspension of the Datsun Sports was very similar to that of the 310 Bluebird, save for an added front stabilizer. This single change nearly doubled the cost. For the Z, they’d use whatever Nissan had lying around.

The L16 engine that was being considered had already seen use in the 510. The single-cam L20 came from the Gloria and Skyline while the dual-cam S20 was also used in the Skyline GT-R. Export markets would get the L24 straight six. This was essentially an L16 with an extra set of cylinders attached. Nissan did have to do a bit of surgery. It did need a longer block, crank, and overhead camshaft, but it was largely made up of existing components. In the book Datsun Fairlady Roadster to 280ZX: The Z-Car Story, Brian Long goes on to say:

“The L16 was a four-cylinder version of the Mercedes-Benz SOHN six, which Prince had built under license before the Nissan takeover. In effect, this new engine was almost the same as the original Benz unit.

The 4-speed manual transmission that would be standard equipment in the American market was derived from the unit from the 510. It was strengthened so that it could withstand the extra power. It also borrowed the front suspension from the Laurel along with a strut from the 510. Even though the Z shares a fair bit with its stablemates, it still manages to carve out its own identity. It’s truly worth much more than the sum of its parts.

Market research was also a critical part of the process. Instead of designing the car in a relative vacuum, the team surveyed their potential customer base to find out what was important to them. They asked about their preferred seating arrangement and interior appointments as well as if they had any interest in an open-top variant. Researchers even broke down the income brackets and lifestyles of those most likely to buy. This helped them focus on specific aspects of the car.

Interior space and ergonomics were major priorities. Optimizing both of these areas would be key to maximizing the car’s appeal. To this end, they created four two-dimensional mannequins that represented American and Japanese males and females. The cars for each market were very similar on the inside, though there were a few minor differences. The steering wheel needed to be moved back a few inches for American-spec Zs. The budget didn’t allow them to make the steering location adjustable. To compromise, they adjusted the steering wheel’s depth by 2.36 inches for cars destined for the United States. Additionally, the seat rails were installed about 3 1/2’’ further back in American cars.

Their work to make the Z more livable would’ve been for naught if it weren’t practical. Nissan wasn’t going after the typical sports car enthusiast. Those people often had other, more practical cars that could be used on a more frequent basis. The company figured that the person in the market for a Z couldn’t afford such a luxury, so it would need as much space as possible so that it could be used on a daily basis.

The team set a target of about 10 1/2 cubic feet of cargo room. Uemura says that this would be enough to accommodate a set of the largest commercially available suitcases as well as two Boston Bags. The Porsche 911 was used as a model for this metric. When the front trunk and back seats were taken together, it had a total capacity of 11.65 square feet.

Conceptual design work traced back to 1965, but the project wouldn’t be formally approved by management until the closing months of 1967. They might’ve been reluctant to add yet another car with sporting pretensions to their lineup. They already had two in the Datsun Sports and Silvia. The former would’ve been different from the Z for reasons stated earlier. The latter was an expensive, hand-built coupe that was not intended for the American market. Even though Teiichi Hara was confident in the business plan, he did not want to take any chances when dealing with management. His account went something like this.

The Nissan R380A-mk2 set seven world records while testing at Yatabe Proving Grounds in October of 1967. Management expressed interest in placing its 6-cylinder S20 engine in one of Nissan’s production cars. The Skyline was up for consideration, but they thought it would be more appropriate in a car like the Datsun Sports. Engineering was given two weeks to come up with a prototype for evaluation. The end result left a bit to be desired. Its wheelbase had to be lengthened to accommodate the larger engine, throwing the overall proportions off.

The higher-ups cooled off on the idea once they laid eyes on it, but Hara had something else to show them. A little ways away was a car under a covering. They removed it to reveal a Z prototype. Hara explained that it could be of interest to them because it was designed around a six-cylinder from the outset. The plan worked. Management officially approved the project in November of 1967.

Several adjustments were made to the plan at this point. They decided to build the Z coupe alongside the Datsun Sports.

To make this strategy work, there would have to be a greater separation between the two lines. The L16 engine was dropped from the Z line. The engine hierarchy will be explained in greater detail a bit later. For now, just know that domestic models would primarily use 2L engines while export models would be equipped with the L24.

Nissan also went full steam ahead on the coupe and ceased development on the other body styles. It was a bit of a shame because the convertible had gotten pretty far along in the process. Five prototypes were made for made to test the NVH and top operation. An open-top car would have obviously encroached upon the Datsun Sports, though there were other reasons for the decision. Increasingly stringent safety regulations in the United States clouded the future outlook of convertibles. There was a fear among automakers that they could be banned outright. Management was also under the impression that a convertible would’ve been too expensive. They even went as far as to cancel a planned sunroof model. The more usable 2+2 was also put on ice, at least for now.

With this step out of the way, the road to production was finally wide open.

ROAD TRIP

The Zs most important test had yet to pass. Nissan did what it could to make sure it could endure the wide range of weather conditions found in the American market. Northeastern states were gripped by brutal winters while the Southwest had to deal with sweltering heat. And that’s to say nothing about the country’s ever-expanding interstate system. There was only so much the company could do without having boots on the ground out there.

This changed late in 1969. A pair of production prototypes were shipped out to Los Angeles. They were to undergo a grueling three-month evaluation to see if the Z could stand up to the challenges. The five-person team also informed the team in Japan of any defects that they came across.

Nissan usually kept these kinds of tests under wraps. For instance, they’d have to conceal the car under a covering and only be able to drive it at night. A special exception was made for the Z. They had permission to test it in broad daylight without any camouflage. Identifying insignias weren’t placed on the cars, so as long as they were tight-lipped about the car, there was little risk of them getting found out. The team was still a bit paranoid, so they asked Nissan America to rent them out a warehouse for the duration of the trial.

Hitoshi Uemura took one of the cars onto Harbor Freeway after one employee reported a rattle during operation. It could only be detected at around 80 miles an hour. Naturally, Uemura needed to drive like a madman in order to maintain that speed. He weaved in and out of traffic lanes and treated the speed limit as a mere suggestion. An unusual noise did eventually come through. Imperceptible at first, the rattle soon became unbearable. He wasn’t exactly sure what was causing the issue, though that was the least of his problems.

A police officer spotted the car and flagged the speeding Uemura down. When he rolled the window down, he wanted to know why he was going so fast. He was perhaps a bit too honest, revealing that he was testing a yet-to-be-released car. He also explained that he was only driving in that manner because he needed to uncover an issue. Then the conversation took a strange turn. Instead of pressing him further on his aggressive driving habits or just writing him a ticket, the cop took a serious interest in the car.

He wanted to know who made it, how much it was going to cost, and when it was set to be released. While the exact starting price never came out, Uemura did say that it would be priced similarly to a standard passenger car. Then the officer looked around the car and said “Really? In that case, I guess I could afford to buy one.” He told him to be more careful out there before letting him off the hook. Considering he could’ve been arrested or had the car towed away, the situation played out very well.

Later on, engineers determined the cause of the vibration. It stemmed from a combination of a dynamic imbalance of the tires and a force stemming from the driveshaft. They worked on a fix for these issues. In the meantime, the test team carried on with their evaluation. The first route on the itinerary was a jaunt through Southern California. With the prevalence of imported cars in this region, many 240zs would certainly find themselves in this environment. It was imperative that the cars would withstand the soaring temperatures.

The team drove both of the test cars through Death Valley. Normally, they’d only take one of them out, but this was done as a safety precaution. They were using a rarely-used stretch of road, so if something happened to the car then they could be in grave danger. Fortunately, nothing went wrong, though they find that the air conditioning was less than adequate. It wasn’t powerful enough to cool the entire cockpit. As a compromise, they devised a system that pointed cold air directly at the occupants. It kept everyone cool, so it was approved.

The next test saw them make the trip from LA to LA. That’s Los Angeles to Louisiana. This 4,300 trek was intended to check its grand touring abilities. It had to be ready to go on a weekend getaway at a moment’s notice. Passes through Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas would also serve as additional heat stress tests.

On the way, Katayama wanted the traveling party to show the car to a certain Datsun dealership. The state it was in wasn’t specified, but based on what happened there I think it was somewhere in Texas. The manager was anticipating them and gave everyone cowboy hats when they arrived. The self-proclaimed “car boys” wrapped up their voyage without encountering any major issues.

The final leg of the test was a 6,200-mile round trip to Dawson Creek in British Columbia that was intended to check the Zs' cold weather endurance. Originally the crew wanted to drive all the way to Anchorage, but they were running short on time. On the way, they passed through Sacramento, Seattle, Vancouver, Edmonton, Jasper, and Banff. Temperatures got to as low as 5 degrees Fahrenheit, which was actually a bit warmer than they were expecting.

About 50 defects were found across their 12,000 miles of testing. Some were addressed, though others, such as the unpleasant highway vibrations, required more drastic countermeasures. These issues notwithstanding, the Z maintained its poise throughout the trial and showed that it could succeed in the market. It was finally ready for action.

NAME

The origin story of how the car earned its name may as well be an urban legend at this point. It goes that Nissan president Katsuji Kawamata saw the musical “My Fair Lady” in 1958 while he was in New York City. He became enamored with it, so much so that the SPL 212 took on the name in 1960(?) The logic was that people that heard the name would make the connection to the Broadway production. It never caught on with Americans. The name was only used there until they received the SP310. At this point, the car became known as the Sports 1500.

Nissan decided to reserve the Fairlady name for SP310s sold in Japan. It made a little more sense to use it out here. In Nissan’s home market, it gave the roadster an international flair. In postwar Japan, where the automotive industry was still finding its footing, this went a long way in establishing the name within the national psyche. It was the perfect name for an aspirational car like that.

The automaker took this even further a bit later in the decade when it set up a gallery at the San-ai Building in Tokyo’s Ginza district. Ben Tsu from Japanese Nostalgic Car likened this part of the city to Times Square in the Big Apple. The “Miss Fairladies” that staffed the trendy showroom had the knowledge and training to shepherd the country’s growing motoring population.

Nissan apparently held an internal naming competition for the upcoming sports coupe. President Kawamata quashed this plan and insisted on selling it under the Fairlady umbrella. Its internal designation of Z would carry over to separate it from its rag-top sibling.

They took a far more conventional approach in other markets. Internationally, it would be known as the Datsun 240Z. The name hints at the 2.4-liter engine under the hood. In the United States, where their cars primarily used numeric designations, it fit right in with the rest of the lineup.

DEBUT

The Datsun 240Z made its first public appearance on October 22, 1969, at the Pierre Hotel in New York. Coverage from the New York Times was rather cut and dry, though it did compare the overall form to Jaguar’s machines. It also earned praise from the LA Times.

The Fairlady Z debuted at the Tokyo Motor Show several days later. Nissan actually unveiled three versions of the car: A base model, a high-performance variant, and the export-spec 240Z. Now is as good a time as any to discuss the Z hierarchy.

It was offered in three trim levels when it launched in the Japanese market. The standard model was priced at 930,000JPY and was equipped with the L20 4-cylinder. This engine made 130 horsepower and 126 lb-ft torque. It also came standard with a 4-speed manual transmission. The more luxurious Z-L started at a touch over 1,000,000JPY and came with a host of features, including a stopwatch clock, reclining seats, and a heated rear screen. It was also the only model in the range equipped with air conditioning to start.

Above that was the Z432. It was the most performance-oriented model out of the bunch. This car was powered by the 2-liter S20 engine that was derived from the unit in the R380. It’s also where its name come from. There are four valves per cylinder, three carburetors, and two overhead camshafts. Horsepower went up to 160 horsepower and torque to 130 lb-ft. This model had a starting price of 1,895,000 and about 420 were built in total.

Topping the Z lineup was the Z432-R. This was an even more focused machine that was built for racing. The radio, clock, glove box, and sound-deadening material were all removed. Acrylic panels took the place of all of the glass, aside from the windshield. Its spare tire was also taken out to make room for a larger 100L fuel tank. All of this resulted in a curb weight of just 1,886 pounds. Total production figures for this model are a bit of a mystery. A 2021 Road and Track article by Brendan Mcaleer says that there were 19 road cars and fewer than 50 examples in total. These are far and away the most valuable S30s in existence. One sold for a staggering 88,500,000 JPY in 2020, which translates to about $800,000.

The Fairlady Z lineup would see a significant change in October of 1971 when they decided to sell the 2.4-liter model in the Japanese market. This version of the car was referred to as the Fairlady 240Z. This also signaled the arrival of the 240ZG.

According to an article from Sports Car Market, Nissan needed to build at least 500 of them in order to satisfy Group 4 homologation requirements. Its unique front end set it apart from the other cars in the range. Officially dubbed the Aero Dyno nose, it featured headlamp coverings and an FRP extension than increased the car’s length by 190mm. It also dramatically improved its aerodynamics. The standard Z had a coefficient of drag of .467 while the ZG had a CD of about .39. The FRP wheel wells also extended the width by 60mm.

Nissan didn’t offer the 240ZG outside of the Japanese market. It couldn’t be sold in the United States for a few reasons. Firstly, the headlamp covers weren’t allowed under the country’s safety regulations. The nose extension also reduced the radiator opening. Apparently, it was available as a dealer-installed option in a bid to make the ZG model eligible for SCCA events. The 2.4-liter engine was only on offer in the Japanese market until September of 1973.

The Z lineup was simpler in the United States. All models were powered by the 2.4-liter L24 engine which had 150 horsepower and 146 lb-ft. It had a starting price of $3,526. For comparison’s sake, the Datsun Sports 1600 cost $2,766 while the 2000 came in at $3,096. It seemed as if there was enough differentiation between the model lines for them to all coexist.

Z production began in the latter half of 1969. Production of both model lines was handled by Nissan Shatai, a subsidiary that also helped build specialty vehicles. Demand quickly outstripped their 2,000 unit per month projection. Interest in the car in the United States was incredibly strong. According to a 1971 Road and Track article, the KBB retail price for a used 1970 model was well over $4,000. If someone wanted a new car, they’d either have to pay above sticker for a model equipped with lots of options or sit around on a waiting list for months. There were even rumors that a dealer had marked a Z up to $10,000.

Nissan couldn’t build them fast enough, even after they raised their production target to 4,000 a month. In August of 1970, they decided to cease Datsun Sports production and convert those lines to building the Z. It was a no-brainer. By this point, they’d sent about 16,000 240Zs to the United States compared to just 1,285 roadsters. After the change in tooling, they’d have the capacity to build 7,500 240Zs a month.

MAGAZINE REVIEWS

It was a smash hit with the general public, but would the motoring press come around to it?

First impressions were quite favorable. Ron Wakefield called it a bargain in the 1970 edition of Road and Track magazine. He praised the generous level of standard equipment and strong performance figures before saying that the thought Datsun had a winner on its hands.

Car and Driver actually got behind the wheel and published their findings in June. They were pleasantly surprised at how well thought out everything was. The driving position and instrument placement were excellent. Its interior appointments also earned high marks, with some testers noting that the cockpit made the car seem more expensive than actually was. Minimal road noise only reinforced these notions. Practicality was also a strong point. The rear hatch revealed a carnivorous luggage compartment that was even fitted with tie-down straps to secure smaller items. Further on, the magazine declared that “the 240Z sets the new standard for utility in 2-passenger cars of this price.”

Actual driving impressions were a mixed bag. It understeered more in right turns than in left turns, though they chalked this up to an isolated incident. That particular car had expanders in the left front spring to overcome a sag. The atrocious directional stability was more concerning. At high speeds, the car would sway left and right. While it wasn’t anything Car and Driver personnel couldn’t handle, it was still unbefitting for a touring car. Spongy brakes made slowing down from those speeds problematic. Stopping power was further stymied in the rain because water could splash into the braking system. Outside of these admittedly serious issues, the dynamics were decent enough. The steering was responsive when it didn’t have a mind of its own and the gearbox was excellent. They thought the 240Z was worth every penny of its $3,601 test price, and potentially more if those shortcomings were ironed out.

Wheels Magazine found that it was an unprecedented value despite lacking the refinement and precision of its contemporaries.

The 240Z even impressed reviewers in Great Britain, which had historically been a tough market to penetrate for Japanese makes. In the March 1972 edition of Motor Sport Magazine, writer Andrew Marriott referred to the car as a “civilized GT carriage.” The no-nonsense IP earned favor with him. It also had little trouble accommodating drivers over 6 feet tall. The author notes that this was an area that Japanese cars struggled with. Perhaps Nissan was trying to appeal to his British sensibilities by sending out a model finished in Racing Green, but it wasn’t necessary. The magazine thought highly of it and lamented the fact that their own country didn’t build a car that was on par with it.

The 240Z had received high praise from the press, but how did it stack up to the competition? Road and Track would find out in April of 1970. It was part of a five-member shootout that contained a few of its closest competitors. The Fiat 124 Coupe had the lowest as-tested price of the bunch at $3,292, and it had a lot to offer on paper. The numbers didn’t jump off the page, but it was the only one equipped with a 5-speed manual and 4-wheel disc brakes.

The MGB GT was getting a bit long in the tooth at this point. It had gone on sale in 1966 and the roadster that it was based on was introduced back in 1962. Still, the British thoroughbred was sure to put up a fight. Its rival from Coventry had a closed-body offering that was a bit newer. Before the 240Z, the Triumph GT6 was the only car among them that had a six-cylinder engine. It was also the smallest, which was sure to make for a raucous combination.

Last, but certainly not least, was the Opel GT. The German import was perhaps the most compromised in terms of practicality. Of course, this also meant that it was the lightest of the bunch. Responsive steering and sharp handling were obvious benefits, but it also achieved an impressive 26 miles per gallon.

Each columnist scored the cars on a scale of 1-10 in terms of their driving dynamics, interior comfort, visibility, and usability. The scores were then totaled from each of them and a winner would be selected. The 240Z came out on top. It absolutely dusted the others in terms of raw numbers. The 124 had the next highest horsepower figure with 104 while the GT6 trailed the Z with 117 lb-ft. Road and Track also recorded a 0-60 time of 8.7, which was far and away the best of the group. For comparison’s sake, the Opel GT clocked in at just under 12 seconds.

Despite this, it wasn’t a complete blowout. The Europeans made up a bit of ground in some other areas and made things somewhat competitive. It just barely edged out the Fiat when the scorecards were added up. That car provided superior steering and handling and even came with a full-size backseat. High-speed performance remained a serious concern. The aero-challenged coupe could lose its composure in the middle of crosswinds. Although the Z still came out of the bout as the winner, its slim margin of victory took Road and Track off-guard. It was the segment leader by a hair, and this would become even smaller as the other cars were redesigned. Nissan would have to continue to improve upon it to maintain its grasp on the segment. The best way to do this was on the race track.

RACING CAREER

The Z was one of the most accomplished racing machines of its day, proving its mettle on the circuit as well as in the rally scene. Datsun was already making a name in the SCCA racing scene in both the east and west divisions. The 510 and Datsun Sports found some success, but the Z would take the brand to heights unseen. Brock Racing Enterprises spearheaded their efforts out west. The club didn’t race for them officially in 1969, they won their division in the SCCA Pacific Coast circuit and earned a spot in the SCCA Nationals in Daytona. Nissan took notice.

Brock met with Katayama and asked if he had an interest in racing under the Datsun USA banner. He believed in the “win on Sunday, sell on Monday” philosophy. Finding success on the race track would help them sell cars and reinforce their image as an exciting company.

Bob Sharp, a race car driver and Datsun dealer, also got in on the action after scooping up a decommissioned show car. It was the first Z to arrive in the US and made the rounds at events all over the country. Its time in the spotlight was cut short after a booth model sat on it during a photo shoot and put a dent in the roof. Sharp planned on giving it a second wind in the SCCA East division.

Alas, the car’s time here was rather uneventful. It suffered a complete engine failure. It could’ve been an isolated incident, but there was also reason to believe that the issue was more widespread. Nissan made a potentially catastrophic oversight. SCCA rules required engines and components that were derived from their production cars. They originally intended to use the Z432 engine in this circuit, but the stipulation drove a stake in those plans. The L24 was not designed for this level of competition. And there was at least one other reason for them to be concerned.

BRE uncovered a harmonic vibration in the engine. The car shook violently under high load, and this was more than a minor annoyance. Peter Brock said that the vibrations were so brutal that the crank severed itself from the flywheel during a test run at Willow Springs Raceway. The team told Nissan of the issue and was met with radio silence. It seemed as if the Zs racing career was over, but the company sent over redesigned components at the 11th hour. After this, the Z stepped in for the Roadster and won several key races down the stretch. BRE punched its ticket to the Runoffs at Road Atlanta and went on to win the 1970 National Championships.

It seemed as if they’d continue to dominate SCCA for years to come, but it wasn’t meant to be. Driver John Morton came away with the C-Production championship in 1971 before the club disbanded in ‘ 73. Bob Sharp, meanwhile, won in 1972 and 1973.

Nissan also bolstered their credentials on the rally scene. One of their first major efforts in this realm was their entrance into the 1970 RAC Rally in London. There was no shortage of teething issues for the burgeoning Works team. Only one of the four competing 240Zs managed to cross the finish line. Still, Rauno Aaltonen’s 7th-place position was decent enough considering the circumstances. If the technical issues were worked out then Nissan could prove to be something to worry about.

Several major events were on the docket for 1971. The elements would not be on their side in Monte Carlo. Blankets of snow and roads slicked with ice would test the skill of both man and machine. While they didn’t win, Nissan did see more than one car complete the race. Aaltonen finished fifth while teammate Fall Tony came in 10th.

The East African Safari Rally was a different beast altogether. It was the most demanding race on the calendar. Machines needed to keep their cool under the sweltering Kenyan sun. The road surface also proved to be a serious obstacle. drivers kicked clouds of dust into the air, obscuring the view ahead for the unfortunate souls trailing them. 91 cars entered the race in 1971 and just 19 managed to finish. While a Nissan did win the event that year, that car was a 1600SSS. There was no telling how the new Z would fare under these conditions. It would be understandable if they couldn’t finish it the first time around.

That is not what happened. Instead, Nissan finished first, second, and seventh. They also made history by becoming the first company to claim the overall victory, team victory, and manufacturers championship in back-to-back years.

MODEL YEAR CHANGES

The 240Z was the right car at the right time. It outclassed its contemporaries in many respects, offering strong performance and unprecedented practicality in an affordable package. It was a smash hit, but how long would this be the case? The 1970s were a period of massive upheaval for the automotive industry. Many 60s sports cars were altered beyond recognition once they crossed into the new decade. Would the same be true for the Z?

Things remained par for the course, at least to start. The first major addition came in the form of a three-speed automatic. Buyers that didn’t want to row their own gears would have to make some compromises for the privilege. Road and Track recorded a 0-60 time of 10.4 seconds as well as a fuel economy rating of 19 miles per gallon. Both of these figures were worse than the standard model. In the real world, they did find that the experience wasn’t that far removed from the stick shift. And at $190, it proved itself as a compelling alternative for those wanting an automatic. It wasn’t a very popular option among the Z faithful. Brian Long states that fewer than 10 percent of cars were optioned accordingly.

Things would soon change for the worse. A strengthening yen rose the cost of many Japanese exports, and the Z was no exception. By 1972, the sticker price rose to $4,106. Safety regulations were also taking a toll on the car. Reworked impact bumpers were installed in 1973, which added about 100 pounds to the curb weight. New carburetors and the inclusion of an exhaust gas recirculation system negatively affected performance. Horsepower went down to 120 horsepower while torque decreased to 127. This was reflected in its slower 0-60 time. Road and Track observed a time of 11.9 seconds for late-1973 models.

Nissan made up some of these losses by increasing the engine displacement from about 2.4 liters to about 2.6 liters. Of course, this necessitated a name change. The car was now known as the 260Z in export markets. Again, the larger engine was not on offer in Japan. Figures shot back up to 162 horsepower and 152 lb-ft, though weight gains and emissions equipment essentially canceled out the performance gains. California models were detuned to 139HP and 137 lb-ft.

Still, car magazines thought it was a better car than the 240Z. High-speed stability and overall handling were much improved. Road and Track even declared that the previous model wouldn’t be missed and that the 260Z amended many of the criticisms that they had of that particular car.

1974 also saw the addition of a 2+2 model. It’s 200 pounds heavier than the 2-seater and the wheelbase is extended by nearly a foot. While the styling doesn’t quite stack up to its sibling, the 2+2 hides the extra weight surprisingly well. Everything looks the part up to the B-pillar. Instead of gracefully sloping back to the rear deck, the roofline abruptly cuts down in an attempt to maintain its sporting looks. It could be better, but it could’ve also been a lot worse. It also had a softer, more subdued character on the road. Reviewers chalked this up to the extra weight and longer wheelbase.

American-market cars saw yet another update later in the year. Units built after September 1st, commonly referred to as 1974 1/2 cars, were equipped with even larger bumpers that increased the overall length by about 100mm. Nissan discontinued it in the US in March of the following year and replaced it with the 280Z. Nissan made it in response to smothering emissions regs in California. The rest of the country was sure to follow its lead. This was a way for the automaker to get in front of the oncoming standards.

As the name implies, engine displacement was increased to 2.8 liters. Performance figures were bumped up to 168 horsepower and 175 lb-ft of torque. It was also the first Z to have fuel injection, which provided several benefits over the previous carbureted models. Cold starts became less of a burden. The system could detect these conditions and supply more fuel until the engine warmed up. It also improved performance, fuel economy, and overall drivability.

In some respects, it was the best the Z had ever been. In others, it was hardly a Z at all. Tumultuous market conditions heavily affected consumer tastes, which in turn influenced how automakers created their products. This much is seen in the gradual evolution of Nissan’s sports coupe. Its curb weight of 2,875 pounds was 520 pounds heavier than that of the original 240Z. The 2+2 added even more weight. The extra heft didn’t stop that particular body style from becoming an integral part of the Z lineup. From 1974 to 1977, the 2+2 made up between a quarter to nearly a third of total sales in the United States. It was also pushed outside of its original price bracket. The 2-seater cost nearly $8,900 in the 1978 model year while the 2+2 started at just over $10,000.

It was far removed from the affordable runabout that it was envisioned as. Even still, the car became more popular than ever. They sold roughly 50,000 cars in 1974. This increased to about 51,000, then 60,000, and then 71,000 in 1977. In addition to showing that consumers still revered the Z nameplate, it also hinted at where the sports car market was headed. With sky-high horsepower numbers seemingly becoming a thing of the past, people became more concerned with efficiency, space, and safety. The 240Z took these into consideration during the design process. They’d have to lean into those traits even further if they wanted to carry this success into the new decade.

Of course, that task would fall to another car. The S30 was discontinued after 1978. It sold over 523,000 units worldwide during its time on the market and spearheaded Nissan’s emergence in the United States. In 1969 they sold just under 87,000 cars. In 1978, they sold roughly 433,000, and there was no sign of them slowing down. Nothing was guaranteed, though.

Competition would be stiffer than ever in the 1980s. Mazda, Mitsubishi, and Toyota would challenge Nissan for the sports car crown at home. The Detroit Three, eager to win back the American populace, will come out swinging with reimaginings of muscle car mainstays. The likes of Porsche and Audi shall throw their hats into the ring as well. I’m even getting reports that a former GM executive will enter the market. And that’s to say nothing of new regulations and experimental technologies. How will Nissan respond? We’ll find out in the 80s!