Honda’s STRANGE Return to Motorcycle Racing

Honda’s meteoric rise through the ranks in motorsports was nothing short of remarkable. In 1954, the company declared its intent to win the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy. Not many took the announcement seriously, considering it was the most grueling motorcycle race on the planet. If Honda did prevail, then they’d prove themselves as an international powerhouse.

They had a strong debut in 1959, proved that it wasn’t a fluke in 1960, and won the event outright in 1961. From here, Honda established a dominant racing program and became one of the most successful manufacturers of the early-to-mid 60s. The likes of Mike Hailwood and Jim Redman piloted their machines to victory. Just as they were etching their names in the pantheon of motoring history, the company stepped away from two-wheeled competition entirely in 1967.

It seemed like a rash decision from those looking in from the outside, but it was actually brewing for quite some time. Honda did everything they’d set out to do in that space. The two-stroke machines that other companies used were also closing the gap with Honda’s four-stroke bikes. Going out on top would’ve looked better than if they were knocked off of their pedestal.

External factors also played a part in their exit. The late 60s were an especially chaotic period for the company. Honda dumped untold time and money into a rather successful Formula 1 campaign and they did not show any signs of stepping away. Production vehicles also took Honda’s attention away from the circuit. Their N360 revitalized Japan’s slumping kei car segment. Using this experience to build a car designed for a global audience was the next logical step. The automotive industry was going through radical changes as well, and Honda needed to dedicate as many resources as possible to that cause if they had any hope of having sustained success in the car industry. At this point, managing a motorcycle club seemed like a distraction more than anything.

While the automotive side of the business flourished in the 70s, Honda’s two-wheeled operations stagnated. They weren’t lagging behind in terms of sales. The company was still the largest motorcycle producer on the planet. In terms of technology, Honda was becoming a shadow of its former self. The workforce in this division had decreased by two-thirds since the early 60s. Other companies saw an opening to knock the Hamamatsu giant from its perch. Yamaha and Kawasaki were expected to put up some stiff competition, but even market failures such as the Suzuki RE5 pushed the envelope. And that’s not to mention the publicity that Honda’s rivals gained on the race track. The company could rest on its laurels no longer.

In November of 1977, a full decade after leaving the circuit, Honda announced its return to GP motorcycle racing. It intended to field a bike in the prestigious 500cc class by the 1979 season. All of this echoed Soichiro’s initial declaration in 1954, with one exception. Honda wasn’t an emerging manufacturer anymore. They were well established at this point, and expectations from the general public were understandably very high. Honda had even more confidence in this new endeavor. They aimed to be world champions within three seasons. The automaker was also able to provide more resources this time around. Honda dedicated a yearly budget of 3 billion yen as well as around 100 employees. It also earned the name of New Racing, which signified the new journey that they were embarking on.

NR500 DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

Honda’s rebellious philosophy has led them to great success thus far. In the 1950s, they blew the motorcycle market wide open with the Super Cub. In the 60s, they released the N360 when other companies were exiting the kei car segment. And in the 70s, they shocked the world with their CVCC technology. It only made sense for Honda to buck the norm for their return to motorcycle racing. To this end, they decided to carry on a decades-long tradition and utilize a 4-stroke engine.

Their obsession with the layout stretches back to the early days of the company. Soichiro Honda despised two-stroke engines. He referred to them as “bamboo tubes” and loathed their dirty, noisy operation. Competing 4-stroke bikes were more powerful and more efficient than Honda’s outgoing 2s at the time. They adopted 4-stroke engines starting with the 1951 E-Type Dream and didn’t look back. They built their dynasty upon that configuration in the 60s, but the racing world had moved on.

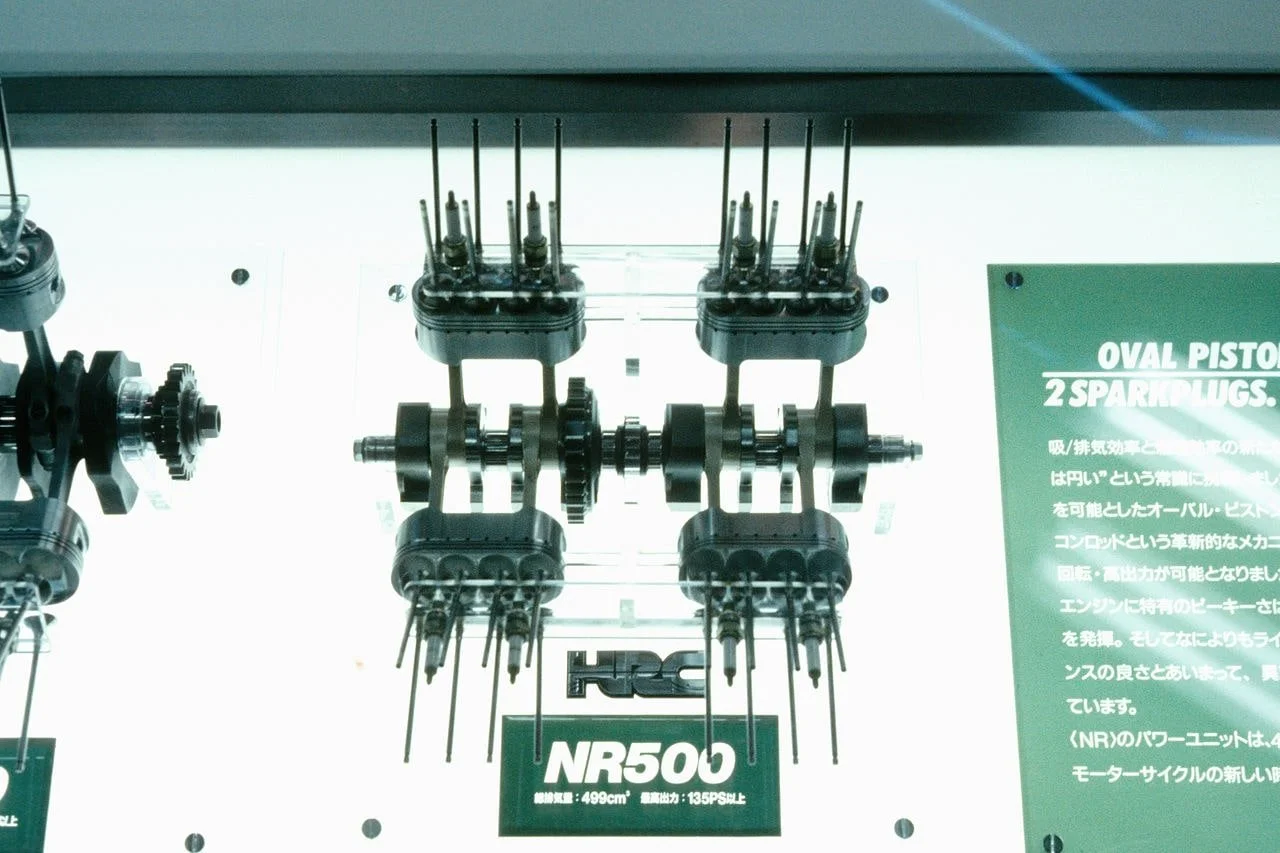

2-stroke motors became the norm in competition racing because they were simpler, more powerful, and more responsive than 4s. Clubs were also incentivized to do so because of regulations. They make power with every rotation of the crankshaft as opposed to 4s, which can only do so on every other rotation. A typical bike makes peak power at about 11,000 RPM. To make the power, a 4-stroke machine needs to make 22,000 RPM. Engine speeds that high would result in excessive heat and friction. To counteract this, The company needed to find a way to increase valve openings above the cylinders. standard pistons could only house up to five of them at the absolute maximum. A V8 engine would double its piston count and allow Honda to make the power at a sane engine speed. Unfortunately, race stipulations limited the maximum cylinder count to four.

Other companies would have taken this as a sign to follow the pack. Honda stuck to its guns and pondered how it could make it all work. If only there was a way to have a 4-cylinder engine with the valve clearance of an 8-cylinder. There was, at least in theory. By changing the piston’s shape from a circle to an oval, they’d be able to achieve the necessary engine speeds. Takeo Fukui, the manager of the Engine Performance Group, predicted that it would be able to rev to 23,000 RPM and have an output of 130 horsepower.

This was a start, though an idea isn’t worth much if it can’t be realized in the real world. The very idea of an oval piston seemed like a fantasy that would remain in the minds of those at Honda R&D. No company had attempted to attempt something like this since World War II. Triumph and Lancia apparently had something in the works, but this was before the conflict, and information on these projects is in short supply. With no third party to turn to, Honda needed to take charge of development itself.

Engineers began working on single-cylinder engines to see if it could even be done. Issues cropped up even at these initial development stages. The connecting rod would distort at speeds above 10,000 RPM, resulting in complete engine failure. The oval piston rings also proved incredibly difficult to build. They were able to work through these problems and had a 125cc prototype finished by July of 1978. They progressed to more complex 4-cylinder engines and completed work on one by April 1979. The engine, internally dubbed the 0X, made 90 horsepower. While this was well below their target of 130 horsepower, it was at least something that they could build off of.

The engine wouldn’t be the only area where Honda would try to innovate. NR member Tadashi Kamiya proposed several ideas for the frame. Among these was a novel aluminum one. The idea was to create a 125cc frame that was capable of carrying a 500cc engine. Colloquially referred to as the “shrimp shell,” the monocoque frame was just 1mm thick and weighed just 5kg, which was about half the weight of a typical tubular steel frame. The engine slid through the back of the machine, an action that Honda likened to a cassette. It was then fastened to the shell with 18 6mm bolts at both sides. The bike also used 16-inch tires instead of the 18-inch tires that were customary on racing bikes at the time. These specially-made Michelin wheels saved an additional 5kg and also reduced the bike’s height by 5cm.

After a grueling development process, Honda completed the basic design work in July of 1979. It earned the name NR500 and made around 110 horsepower at 16,000 RPM. Now it was time to go racing.

RETURN TO THE CIRCUIT

Although the development process was full of issues, Honda was hopeful that it would be ready to debut sometime in the middle of the GP season. Unfortunately, there were unexpected delays that pushed its start date all the way back to the British GP in August, the second-to-last race of the season. It seemed to be a lost year, though Honda still wanted to get some race time in before it ended.

The automaker signed two riders to assist in the development of their machines. Mick Grant came on to the scene in 1969 and spent time with Norton and Kawasaki before coming over to Honda. Grant’s most notable achievement thus far in his career came at the Isle of Man in 1975, when he broke Mike Hailwood’s then 8-year-old fastest lap record by going around the course at a speed of 109.82mph.

Takazumi Katayama, meanwhile, became a Yamaha factory drive-in 1974. He then competed in the 1977 World GP series and won the championship in the 350cc class. In 1978, he finished second in the standings. Honda signed the red-hot racer into their team the following year. While the company wasn’t expecting a win at Silverstone, they at least hoped for a strong debut with riders this accomplished.

No one at Honda was under the impression that the NR500 was ready to compete. Its appearance at the British GP was meant to be a demonstration more than anything. They didn’t want the riders bringing up the rear, so they only gave the bikes enough fuel for a few laps. It would let Honda see how they held up to competition and give enthusiasts something to get excited about.

“They didn’t want me and Katayama coming last and second-to-last, so they told us they only put in enough fuel for a few laps and to put on a bit of a show then stop.”

But that’s if the bikes could make it to the starting line at all. They were starting to lose their composure leading up to the race. Honda race staff worked around the clock to keep the machines together. While one team worked on the bikes at the track during the day, another party would take them into the shop and work on the engines into the morning.

Grant and Katayama just barely made the cut during qualifying, but at least they were in the mix. Anything could happen once the checkered flag fell. What’s more, Soichiro and Sacchi Honda made the trip out to see the brand’s return to racing in person. The pressure was on to make a good first impression in front of the company’s founder.

Well, this is awkward. Oil spilled over Grant’s rear wheel, causing him to fall and ultimately resulting in a small fire. Needless to say, he was forced to retire. While this was an unfortunate development, it wasn’t the end of the world. The rider was unharmed and Honda had another rider on the circuit. Katayama could still provide them with valuable data. He just needs to get around the course a few… oh. I had no idea this was going to happen you have to believe me. An electrical issue forced him into the garage and eventually led to his untimely exit. And just like that, Honda was out of the race. This was just about the worst way that their debut could have gone, and to make matters worse, only one event remained on the schedule.

Honda’s hopes were crushed for good at the Le Mans Bugatti circuit in France. Both bikes failed to qualify for the main event. Head engine designer Toshimitsu Yoshimura took it especially hard. He couldn’t even bring himself to review the race footage when asked. After their humbling experience during the 1979 season, they realized just how far away they were from their goal.

PEAKS AND VALLEYS

The NR team was determined to improve the 500 for the 1980 season. They had a look at the engine, but not for the reason you might think. Excessive engine braking resulted in rear wheel hop and general instability. Honda utilized a slipper clutch to counteract this. It partially disengages when engine speeds eclipse a certain range, keeping the bike on the track and imparting more predictable driving dynamics. The weight of the 0X engine also increased by as much as 20kg as they tried to increase its durability. Engineers made use of titanium and magnesium throughout in an effort to lighten things up. Honda noted that this advantage was short-lived because other manufacturers took on this amalgam of metals.

While these changes certainly made the NR500 a more competitive bike, they did little to address its largest handicap; the 4-stroke cycle. The company remained committed to it, even if it meant it’d be at a natural disadvantage to its competitors. The shrimp shell frame also became more trouble than it was worth. Its cassette-style engine bay turned on-track tuning into a frustrating and time-consuming chore. As a result, Honda used a more conventional steel frame by Ron Williams in 1980.

Development work on the revised NR500 bled well into the season. Honda wasn’t able to line a bike up until the Finnish Grand Prix late in July. It was the 6th race of the season, and to make matters worse, there were only two races after this for the 500cc class. The year was a lost cause. Honda only had one more season to make good on its internal declaration. They desperately needed to build momentum going into ’81 if they had any chance of becoming world champions. That would have to wait, however, as Katayama received a DNS. Honda remained undeterred and focused its sights on the next event at Silverstone. Spectators wondered if memories of last year’s outing would linger, but the club put these concerns to rest. The NR500 finally managed to finish a race as Katayama finished in 15th place.

Its greatest challenge had yet to come. For the final race of the season, the Honda would have to navigate 8 laps around the vaunted Nürburgring. It wouldn’t be easy, but if they could manage to get through Green Hell, then they’d exit the season on a relatively high note. Honda did just that by coming in 12th place, their best result yet. While they didn’t yet have any points to their name, they did unearth a glimmer of hope in an otherwise disappointing campaign. Maybe the prospect of a world championship wasn’t so farfetched after all.

They continued where they left off in 1981 at Austria. Katayama finished in 13th place. Points remained frustratingly out of reach, however. Perhaps they’d catch fire in the middle of the season and make things interesting.

The West German GP was a bust, as Katayama flamed out after just four laps. Honda retired at Monza and Paul Ricard as well. They didn’t participate in the Yugoslavian GP but had a chance to finish strong at Assen. Katayama managed to work himself into 10th place with just one lap to go. disaster struck before Honda could tally its first championship point, however. The NR500s spotty reliably undid them, as its ignition gave way and knocked them out of the running. This defeat rocked the team to its core. They were willing to try anything at this point, as Honda International Racing Company boss Gerald Davidson said in a 2022 Motorsport Magazine article.

“I was having a lot of long talks with Iri-san, [Irimajiri],” recalls Gerald Davison, boss of HIRCO (Honda International Racing Company), which was established to run the NR project. “Half joking, I told him he should send the NR people to a temple and tell them to really reflect on what they’re trying to do. The very next day he did just that! A fleet of minibusses took 40 of us to a Buddhist temple. We also took along some bits of the bikes that would receive blessings. So we arrived at this beautiful place, up a forest-clad mountain, with dancing girls and music. It was all pretty spectacular.”

Earning the chip would’ve taken nothing short of a miracle at this point. Honda was, unfortunately, resigned to its fate. Five races remained on the calendar, and they couldn’t finish a single one. The company spent the entirety of its return to competition in the basement. Instead of popping champagne and gearing up for a title defense, the New Racing team doubted itself and wondered what direction they should take next.

QUEST FOR REDEMPTION

Honda fell short in its quest for glory, but it couldn’t give up now. Their woes on the circuit weren’t exactly a secret. Leaving on such a low note surely would have negatively affected their reputation and sales. They had no choice but to try and salvage their racing operations. And they’d start by finally acknowledging the elephant in the room.

Honda needed to leave the past in the past and finally adopt a 2-stroke layout. At the same time, they didn’t want to take the same approach that the other clubs were taking. If Honda truly wanted an advantage, then they’d have to think outside the box. Development kicked off in the middle of the 1981 season.

Engineer Shinichi Miyakoshi was tasked with designing the new engine. He attended the 1981 Dutch GP to observe the machines in person and made an interesting discovery. The 500cc bikes and 350cc bikes had very similar lap times. This gave him the idea of a motorcycle that had the power of the former as well as the nimbleness and compactness of the latter.

To support this philosophy, he proposed using a lightweight V3 engine. Most other bikes were powered by 4-cylinder engines. While they provided more power, they were also heavier and more complex than Miyakoshi’s envisioned engine. It had a max output of 120ps at 11,000 rpm which, while still a bit behind its 4-cylinder rivals, was in greater harmony with the rest of the bike. Honda also improved its cornering ability by reducing its wheelbase by 25mm.

The new NS500 was ready for the start of the 1982 season. Katayama, eager to try his hand at the reimagined 3-cylinder, returned to the club this year. Alongside him was Marco Lucchinelli, who won the 1981 championship on a Suzuki. Ron Haslem would also be piloting the old NR500. The final rider on the team was a relative newcomer to the Grand Prix scene: Freddie Spencer.

The Shreveport, Louisiana native rose through the AMA Superbike championship during the late 70s and early 80s. When Honda joined this league in 1980 they brought Spencer on as a factory racer. He continued his run of success this year, and in 1981 they had him split time between AMA Superbike and the World Motorcycle Championship. His results in this first year weren’t all that noteworthy. In the 1981 British GP, he worked his way into 5th place before the NR500 let him down. Spencer would be racing in Europe full-time in 1982, and Honda hoped for better results on a more reliable machine.

He gave them a taste of what was to come at the first race of the season in Buenos Aries. He finished in third and was just 1.3 seconds out of first. Lucchinelli came in 5th place while Katayama was right behind him in 6th. Honda earned their first points since its return to GP racing and showed that it had a real chance at winning the title. In order to do that, they’d have to take down the current powerhouse in Yamaha.

That company’s effort was spearheaded by Kenny Roberts, one of GPs rising stars. He joined Yamaha in 1978 after a successful run in AMA dirt track racing. When he won the title that year, he became the first American to do so. He followed this up with two more championships. Lucchinelli, then a member of Suzuki’s team, came away with it in 1981, though Roberts was still a threat for the crown. After all, he already claimed victory at Argentina.

Roberts finished third at the next event in Austria. Katayama wasn’t very far behind, coming in 9th place. Honda’s machines remained competitive going into the 7th race of the season in Belgium. Spencer rode his second-place qualifying result into a convincing victory, making him the youngest rider to win a 500GP race. Honda found the top position a month later, with Katayama besting the runner-up Suzuki by nearly 8 seconds. Spencer earned a dominant win of his own in San Marino. With consistent success like this, one might assume that Honda was in contention for the GP title. That was not the case. Franco Uncini ran away with it, winning by a staggering 27 points. Spencer finished third while Roberts and Katayama came in 4th and 7th, respectively.

1983: A RACE ODYSSEY

1983 was shaping up to be a critical year for the program. Honda went from a non-factor to a serious threat for the title. The pressure was on for them to finish the job. What’s more, Kenny Roberts announced that this would be his final season in Grand Prix competition. He’d do everything in his power to ensure he’d go out on top. No matter how the results panned out, one thing was for certain; ‘83 would be a year for the ages.

Spencer made quite a statement by claiming the first three races of the season, but Roberts was right on his heels. They finished 1-2 at both Kyalami and Monza. In France, Roberts finished behind a trio of Honda riders. While he had yet to take victory, he was still in a prime position to make a move in the rankings.

This is precisely what occurred at Hockenheim. His 4-cylinder Yamaha took full advantage of the straightaways en route to a first-place finish. In any other circumstance, Spencer’s 4th-place result would have been something to be proud of. In this fierce duel, it simply wasn’t good enough. He earned a bit more breathing room after his victory in Spain. The Americans traded the next two races before Roberts captured three consecutive victories. He pulled within two points of Spencer going into the Swedish GP.

The fates of both clubs hinged upon this event. If Spencer won, he’d have a five-point cushion with just one race remaining on the calendar. This slim advantage would guarantee him the championship even if he finished in second. A win for Roberts would give him a razor-thin one-point lead, and while it would be a tough ask to finish strong at the following race, he’d at least have control of his own destiny.

Spencer and Roberts pulled ahead of the other riders and engaged in their own battle. Anderstorp was full of straightaways that gave a slight edge to the Yamaha. It seemed as if he’d carry that advantage all the way through, but then, at the last moment, this happened.

Spencer won by the skin of his teeth. His margin of victory was just .16 seconds. The title was all his, provided he had a strong finish. As previously stated, he’d have the highest point total at the end of the season even if Roberts finished ahead of him. But what if he finished third? The two riders would have the same number of points and they’d have to look toward tiebreaker scenarios. The title would go to whoever had the most 2nd place finishes. Roberts had three this season while Spencer only had two. He’d win it all in this case, so the pressure was on their teammates to keep the NS500 in third.

Although Roberts did well in qualifying, he found himself in the middle of the pack once the flag fell. The Hondas, meanwhile, had an especially strong start. He desperately needed to make up ground if he wanted any hope of winning the race. In time, Roberts broke away from the pack and soon overtook Luccinelli for second. He lurked in Spencer’s shadow and waited for an opening.

On the 8th lap, right after the high-speed bend near the starting line, Roberts made his push. He overtook the Honda coming out of the Tosa corner. He’d done his part, but the job wasn’t finished quite yet. One of his teammates needed to get in front of Spencer and stay there. This would be much easier said than done. He was well aware of the situation and did everything in his power to hold on to his second-place position. Although Yamaha’s Eddie Lawson was right behind him, he couldn’t get close enough to pose a true threat. Roberts and Spencer were in a class of their own.

It was a hollow victory for the leader. Roberts might’ve won the battle, but Spencer came out of the brutal GP season as the victor. At just 21 years old, he also became the youngest grand champion ever. The manufacturer's title went to Honda as well. All of this was thanks to boundless ambition, unconventional thinking, and an unending desire to innovate. Honda never strayed from its philosophy, even after the failure of the NR500. A full 16 years after stepping away from the circuit, they were champions once again.