Marcello Gandini: Father of the Lamborghini Miura

Marcello Gandini’s crowning achievement was the Lamborghini Miura, which some consider the most beautiful car ever made. While it wasn’t the first model to bear the raging bull, it was the one that truly set the emerging make apart and thrust the young designer into the spotlight. The Miura was just one of many iconic cars to come from his pen. During his decades-long career, he designed some of the most important automobiles in history and spearheaded the aesthetic of an entire generation.

MARCELLO BEFORE BERTONE

Marcello Gandini was born in Turin on August 26, 1938, mere weeks before Giorgetto Giugiaro and a few months after Leonardo Fioravanti. Marco, his father, worked in the pharmaceutical industry, though music was his true passion. In addition to his day job, he also made a living as an orchestrator. Marco nudged his son to follow in his footsteps. From the age of four, Marcello began learning to play the piano. He grew to resent this, as he told Top Gear’s Jason Barlow years later. While the other kids were playing outside, Marcello was stuck at home, his head buried in sheet music. Marcello’s interests took him down another path.

A lifelong love of cars and design took root at an early age. The book Marcello Gandini: Maestro of Design by Gautam Sen says that he spotted a Cord on one occasion. It was unlike anything he’d seen on the road. In the age of running boards and chrome, the Cord stood alone. It’s little wonder why Marcello was so taken by it.

His family also gifted him an erector set. With these kits, kids could assemble automobiles, heavy machinery, and everything in between. Marcello came to realize that design was about much more than aesthetics. What was under the skin became just as, if not more, impressive to him. This appreciation of art and science would be perfect for a career in automotive design.

Gandini took a rather unconventional approach to get into the industry. Instead of pursuing an education, he dropped out and struck it out as a freelancer. Some jobs were right up his alley. A friend hired him to modify his OSCA 1500S for competition, giving Gandini a taste of what automotive design could be like. Other assignments were outside of his comfort zone. He dabbled in furniture design and even did the interior of The Crazy Club, a local late-night establishment. These tasks did more than put food on the table. They broadened his horizons and helped shape him into a more well-rounded designer.

Soon enough, Marcello worked up the confidence to show his drawings to the many coach builders in Turin. Nothing came of this until a friend got him in touch with Bertone. Nuccio, the man in charge of the firm, already employed a talented designer in Giorgetto Giugiaro. Although he didn’t offer him a job at that point, he remained intrigued and told him that they’d be in touch soon. Gandini would be waiting for quite some time. Gautam Sen’s book mentions that the two of them happened to run into each other in 1963. Nuccio apologized for not reaching out but informed him that bringing him on would likely cause Giugiaro to leave the company.

While this was a disappointing development, Nuccio’s earlier encouragement did seem to give Gandini more confidence in his abilities. In 1965, he landed a job at Carrozzeria Marazzi. Later that year, Nuccio got in touch out of the blue and offered him a job. Giugiaro was set to leave for Ghia, and Bertone needed someone to take his place. If Gandini took the job, then he’d be stepping in as chief designer. He wanted to accept it, but prior engagements at Marazzi prevented him from doing so. As a compromise, he suggested that he start out working for Bertone on a consultancy basis. On November 1, 1965, Marcello Gandini began working for the company full-time.

The 1966 Geneva Motor Show would be one to remember for the design house, for it had three cars scheduled to debut. Ferruccio Tarchini, an Italian Jaguar importer, commissioned Bertone to style a 5-seat coupe based on the S-Type 3.8. The FT 3.8, as it was known, was a largely unsuccessful effort. Much of this stems from the tall greenhouse, which makes the car feel unbalanced and ponderous. The grille is another misstep. Designers attempted to incorporate a version of Jaguar’s corporate grille. The execution leaves much to be desired. It isn’t tall enough to add presence like on other models, but it also isn’t wide enough to emphasize the car’s width. When compared to the two other Bertone-designed cars, the FT is lacking in style.

The second car from them was also a commission. Porsche’s venerable 356 was set to be replaced by the 911, and with it would go the popular speedster. Management decided against developing a direct successor to this variant. The 911 was not designed to be a convertible. Porsche even brought Karmann in to create one and found that serious compromises would have to be made in order to make it work. The rear engine layout meant that there wouldn’t be a place to store the top; it would have to simply fold back above the engine, similar to the Volkswagen Beetle Cabriolet. At the 1965 Frankfurt Motor Show, the company unveiled the 911 Targa to serve as a compromise of sorts.

Johnny Von Neumann, the brand’s distributor in Southern California, didn’t think that it would sate fans of the 356 Speedster. His words carried more weight than your average Porsche dealer. The Speedster that had been such a success was the brainchild of he and Max Hoffman. If anyone knew what buyers in the region wanted, it was him. Porsche still wasn’t very receptive to the idea but gave Neumann a chance to prove himself. It authorized the creation of a single car to serve as a feasibility study. Although he’d be funding the project out of his own pockets, the company would have the final word on whether or not it got the green light.

Neumann went to Bertone with the brief, which had the Porsche 911 Roadster concept ready in time for the show. The two parties agreed that it should bear no resemblance to a standard Porsche, and it shows. It trades in the exposed, upright headlamps for a quartet of bulbs partially hidden behind a retractable cover. The outermost lights are partially exposed to flash oncoming traffic. When additional illumination is needed, the covers don’t pop up, but slide down into the bodywork. They also give the Roadster a distinctive front-end signature. Gandini would incorporate headlight covers into many of his future designs to achieve the same effect.

Bertone also modified the interior. The five gauges were moved from behind the steering wheel and are arranged in a T-pattern on the dash and center panel. While this lowers the cowl height, it also requires the driver to take their eyes off the road in order to read the information. This dial on the passenger side is especially concerning. It’s well out of the way and partially obscured by the dash.

Development on the car dragged on for 9 months. Work didn’t wrap up until mere hours before the show. Last-minute finishes would become a pattern for Bertone. The car generated some buzz at the Geneva Auto Show, but with an estimated price of just under $8,000, there wasn’t any serious interest. Extensive modifications to the interior and exterior shot the price into the stratosphere. Meanwhile, Porsche had the 911 Targa on display in its own section. That car had a sticker price of $6,170. The way forward was clear: a convertible 911, as appealing a prospect as it was, simply wasn’t viable.

LAMBORGHINI MIURA ORIGINS

The Jag and the Porsche paled in comparison to the true star of Geneva, the Miura. Lamborghini had made a bit of headway in the automotive world with the 350GT. The touring coupe gave Ferrari some healthy competition, but engineer Gian Paolo Dallara wanted to make something more extreme. Before coming to Lamborghini, he worked for Ferrari and Maserati, brands with storied racing programs. Mid-engine cars had become the norm on the circuit, but the layout hadn’t trickled down to production vehicles. Enzo Ferrari didn’t think that his customers would have the skills to keep a mid-engine car on the road.

Dallara was free to experiment at Lamborghini. The likes of the Ford GT40 and Ferrari 330P would have been obvious inspirations, but he was motivated by another, unlikely car, the Mini Cooper. Journalist Winston Goodfellow spoke with Dallara about the Miura’s development. He went on to say, “The original idea was to use that Mini’s ingenious front-wheel-drive engine and transmission and place it behind the driver to make a mid-engine car.”

After developing the concept for some time, he went to Ferruccio and asked if he was interested in getting more parts from Mini so they could build the cars at scale. The boss had a better idea. Instead of putting out a parts bin special, he wanted them to take the idea to another level. He allowed Dallara and fellow engineers Paolo Stanzani and Bob Wallace to work on a proof of concept.

It would use the same Bizzarrini-designed V12 from the 350GT, but it would be mounted transversely behind the seats. It brought the weight inward and freed up enough space for a 5-foot cargo area at the rear of the car. They spent six months working on the engineering drawings, and a prototype was completed soon after.

Lamborghini asked Carrozzeria Touring to skin the car in September of 1965. The two entities had worked together on the 350GT, so they hoped that this collaboration would produce equally pleasing results. Touring produced two asymmetrical scale models, with each side showing a different design, making for 4 proposals in total. None of them impressed Ferruccio. With the Turin Motor Show approaching, the company decided to put the bare chassis on display.

MIURA CHASSIS DEBUT

It debuted bearing the TP400 moniker. The acronym, short for transversal posteriore, is Italian for rear transversal. It seemed like representatives from every coach builder in town came by to have a look. Bertone was the only firm that didn’t stop by during the initial rush. When Ferruccio asked what took so long, Nuccio said that he wanted to wait for the crowds to disperse. Ferruccio then asked, “Do you not wish to design the body for my new car?” Nuccio responded, “I will pen the perfect shoe to fit such a wonderful foot.”

Several factors played into Ferruccio’s decision to go with Bertone. Firstly, Carrozzeria Touring was on shaky financial ground, and Nuccio’s company seemed to be the safer bet. They were also practically the only coachbuilder without any major ties to Ferrari. Perhaps the aspect that stood out the most was the sheer quality of their work. Ferruccio took a liking to the Alfa Romeo Canguro and sought a design of that caliber for his car. He didn’t realize that Giugiaro, the man who styled that car, had left the company some time ago, and in his place was a 27-year-old who hadn’t yet proven himself in the industry. There was also the issue of time. Lamborghini needed the car ready for the Geneva Auto Show, which was a mere 4 months away.

BODY DESIGN DEVELOPMENT

This aggressive deadline forced Bertone to kick the development process into high gear. Engineer Piero Stroppa created a package drawing of the chassis on the 20th of December. Gandini, no doubt sweating out the strict time restraint, hashed out the profile directly on top of them. Orthogonal drawings were completed on Christmas Eve, and several days later, Ferruccio approved the design.

Work on the prototype began in January 1966. Many of their processes overlapped with one another. For example, the wooden buck that they’d use to shape the body panels was being assembled at the same time the 1:1 drawings were being completed. The firm was also juggling the Porsche and Jaguar projects. The fact that they had all three ready to show in Geneva was nothing short of a miracle.

Nuccio Bertone was said to have had significant input on the design. The legend goes that Gandini largely ignored his suggestions. With the design finished and the prototype two weeks out from being completed, Gandini took a vacation. While he was away, Nuccio made his layover to the studio and made a few changes to the design. What these supposed alterations were, exactly, has been lost to time. When Gandini returned, the finished prototype was in the process of being painted. He was taken aback, but there was no time to reverse the changes.

This story has since been debunked. In Gautam Sen’s book, fellow engineers Stroppo and Prearo maintain that no changes were made to the design. Nuccio’s suggestions started and ended with his suggestion to use lighting components from the parts bin. Moreover, Gandini didn’t go on vacation until the Miura was completely finished and on the way to the event.

MIURA DESIGN OVERVIEW

The retractable headlights lie flush with the body to reduce drag and tilt up slightly when activated. Gandini heeded Nuccio’s suggestion to use existing parts and pulled units from the 850. Thin forks are placed at the top and bottom of the enclosure. Enthusiasts commonly refer to them as eyelashes because of how they curve onto the body.

Thin bumper strips are located at the front and rear of the car. They’re deemphasized even further because they’re integrated into larger grilles. One thing you won’t see on the body is a door handle. They’re the very bottom slats in the intakes just inboard of the doors. The prototype car had a plexiglass cover over the engine, but there were visibility and ventilation issues. Production cars had louvers that kept the engine dry and preserved the sliver of visibility that remained.

At the rear, we can see the first appearance of a styling feature that both Lamborghini and Gandini would utilize heavily in the future. The lower half of the rear clip has a hexagonal pattern. The pattern is elongated to allow as much air into the engine as possible. Gandini went into his thought process a bit more in an interview with Car and Driver, saying that it “was a way to characterize the functional elements, such as the grille.” In this case, it calls attention to the opening and emphasizes its. Hexagons would continue to show up in his work. And right above this are tail lights that were also borrowed from the Fiat 850.

MIURA ROADSTER

A roadster version debuted at the 1968 Brussels Motor Show. It received a warm reception, but Lamborghini decided not to put it into production. It sold the car to the Lead Zinc Research Organization, which sought a car that they could use to showcase their lightweight materials. The automaker didn’t want to give them a car off the line, though it was willing to part with the one-off. Its time on the auto show circuit had come to an end, and the company was happy to get anything out of it.

Lead Zinc dismantled the car, repainted it green, and replaced many of the stock parts with zinc alternatives. Lamborghini’s discarded concept car was used as a promotional tool for a decade, after which it was sold to a private buyer. In 1980, the Brookline Museum of Transportation received it as a donation. Several more owners took possession of the car before it came into the hands of New York property developer Adam Gordon. He oversaw an extensive $320,000 restoration that reverted the Miura Roadster back to its original specification. It earned second place at the 2008 Concours d’Elegance. Later that year, he sold it to a private buyer for an undisclosed price.

LAMBORGHINI MARZAL

Ferruccio handed Bertone another assignment after the Miura project concluded. He wanted a round out the lineup with a full-size 4-seat coupe. At the 1967 Geneva Auto Show, the company unveiled the Marzal concept. Bertone used a modified Miura chassis as a basis, lengthening it by 120mm to accommodate a set of rear seats. The new engine freed up even more space. Well, it wasn’t really new. Engineers chopped the Miura’s 4L V12 in half, creating a transversely mounted inline-6 that made 175 horsepower.

The gull-wing doors are the Marzal’s most distinctive design element. They grant access to both the front and rear seats. Just as unusual is the sheer amount of glass. It has over 49.5 square feet of the stuff. The tall greenhouse has a way of ‘pulling in’ the rest of the body, making it feel a touch more compact. Door guards that come from the front end break the mass up and guide the eye around the car. They surround the car at its widest point, giving the brittle material a bit of protection. Ferruccio was not a fan of the glass doors because they provided the occupants no privacy. He even said, “A lady’s legs would be there for all to see.”

The honeycomb pattern continues into the interior. It’s directly referenced in the dash, but it can also be seen in the shape of the instrument cluster housing and storage compartment on the passenger side.

Gandini touched on the Marzal during a 2018 interview with Top Gear. He said: “Basically, the Marzal was drifting towards what science-fiction writers had been promising. With these prototypes, a public declaration was our way of seeing the cars of the future.” It may have been a bit too avant-garde for Ferruccio, but the idea of a 4-seat Lamborghini still intrigued him. A more grounded interpretation of these ideas wasn’t far off. Only, the car wouldn’t be bearing the raging bull, but the leaping cat.

JAGUAR PIRANA/LAMBORGHINI ESPADA

John Antsey, the editor of the Daily Telegraph, went to Bertone and commissioned the Jaguar Pirana. That’s how it’s spelled: without the H. The coachbuilder originally used the correct spelling but tweaked it because the other name was already in use. Development lasted six months, and the Pirana made its first appearance at the 1967 London Auto Show.

The outlandish elements from the Marzal have been left on the cutting room floor, but for the most part, the DNA largely remains. Its sextet of headlights has been swapped out for more conventional halogens. The front-end signature loses some character as a result. Whereas the Marzal was mid-engine, the Pirana has an FR configuration. The door guard is also gone, replaced by a character line that follows a similar path. Even the rear wheel well treatment is identical.

Lamborghini unveiled the Espada in 1968, finally bringing the principles introduced with the Marzal and Pirana to a production car.

ALFA ROMEO MONTREAL

Alfa Romeo was invited to present a car at the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal. They, in turn, gave Bertone a Giulia chassis and asked them to work their magic. A pair of show cars were sent out to the event. It was originally intended to make them mid-engine, but due to time constraints, they needed to pivot. They used the Alfa Romeo 1600GT as a foundation. Over 55 million people attended that year’s event. Legend has it that the reception for the cars was so overwhelming that Alfa Romeo had no choice but to greenlight them. Martin Buckley from Classic and Sports Car theorizes that production was probably in the back of the company’s mind the whole time.

Delays and labor disputes pushed the release into 1971. The Alfa Romeo Montreal carried over the main beats, but the details have changed considerably. The headlight coverings are one such modification. Classic and Sports Car states that the ones on the concepts could be adjusted to meet different light height requirements in different markets. On the production car, they’re purely for show.

Styling in general has changed, with the concept being a bit leaner and curvier and the production car feeling more blunt and solid. The chin, side windows, and faux vents are the major elements that were tweaked. The concept also had a set of vents near the base of the windshield that tied into the openings on the side. Conversely, the road cars have a large NACA duct on the hood. These changes amp up the aggression at the cost of some finesse.

The concept may have been the darling of the expo, but the road car was a sales disappointment. Alfa Romeo didn’t certify it in the United States due to emissions concerns, which outright eliminated a major market. The oil crisis struck about halfway through the product cycle. Touring coupes of all varieties suffered as a result. Somehow, the Montreal endured through 1977. According to Autoweek, total production was a touch over 3,900.

BMW SPICUP 2800 CONCEPT

1969 saw the debut of the BMW Spicup Concept. Its name is in reference to the trick roof and is a portmanteau of the words “spider” and “Coupe.” Basically, the front portion slides into the back portion, which then goes into the roll bar. The finish pops against the emerald green paint. The same treatment is applied to the engine scoop on the hood, suggesting immense power.

The roof was just one part of a very unconventional design for a BMW. Just about the only thing that calls back to the brand is the kidney grille, and even the treatment there is unconventional. The innards pillow out, almost as if it’s doubling as a protective bumper. Flanking it are two horizontal elements. BMW models of this vintage used a similar arrangement, though again, Bertone has played with the formula. They’re lined with the same material and also have a mirror-like finish. And just like the Montreal and 911 Roadster that came before, the Spicup has partially covered headlights. Unlike those cars, they pop up instead of sliding into the bodywork. A tossable two-seat convertible would’ve complemented BMW's range of sedans and coupes nicely. Tragically, the automaker decided against putting it into production.

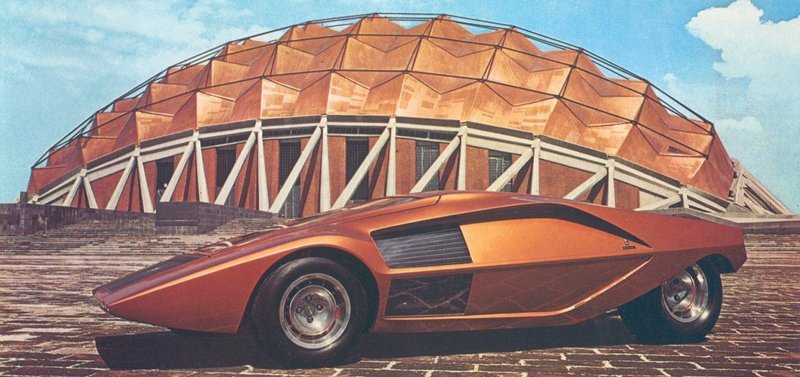

ALFA ROMEO CARABO

The Alfa Romeo 33 Stradale is one of the most beautiful cars ever designed, but at a price of $17,000 new, the company had trouble selling them. Of the 18 that were built, five were handed out to various coachbuilders. One went to Italdesign, two went to Pininfarina, and two went to Bertone. Gandini’s firm re-bodied one of theirs in 1968.

The Alfa Romeo Carabo is both a design exercise and a design study. Although the Miura was well-received upon its debut, magazine reviewers found that it had a tendency to lift off the ground at high speeds. The Carabo was created, in part, to mitigate that issue. Its name comes from the carabidae beetle.

The Carabo bucks the 33 Stradale’s flowing lines for a chiseled, dramatic form language. Its nose quite literally comes to a point. From there, the silhouette goes to the rear nearly unimpeded. The long, exaggerated front overhang and the short, blunt rear overhang help to give the impression that the Carabo is slicing through the air while standing still. The form is preserved even when the headlights are activated. Six panels up front flip up in a way that doesn’t disrupt things too much. They also contrast with the hood scoop.

It’s 165 inches long, 70 inches wide, and under 40 inches tall. Egress would have been a challenge with conventional doors, so Gandini needed to find an alternative solution. The answer came in the form of its scissor doors. They’re hinged at the front and raise straight up. I don’t think I need to go through how iconic and influential they have become.

The Carabo is one of the most influential concept cars in automotive history. It guided Gandini’s philosophy for decades to come and ushered in a new era of transportation design.

AUTOBIANCHI A112 RUNABOUT

Bertone finished out the year with the Autobianchi A112 Runabout. Fiat had called on the design house to assist in the development of the 850 Spider. It saw some success in the market, but they wondered what it could be like if it weren’t tied down by the rear-engined 850’s bones. Bertone, being familiar with creating midship designs, proposed such a configuration for the new car.

The Runabout looked outlandish, but its underpinnings were very much grounded in reality. Essentially, Bertone took the front-engine, front-wheel-driver foundation of the 128 and flipped it around, creating a mid-engine, rear-wheel-drive plan. The new setup improved weight balance by allowing for the spare tire and fuel tank to sit behind the rear seats.

Heavy powerboat influences are present in the styling, as seen with the angled roll bar, metallic undercarriage, and low windscreen. It almost looks as if it’s ready to spend a Saturday afternoon out in the water at Lake Tahoe. Oh, and those lights at the edges of the front end aren’t the main ones. They’re actually placed alongside the roll bar.

The Runabout never saw production, but Fiat became convinced of the benefits of the new layout. A new car utilizing the lessons learned from the concept turned up in 1972: The Fiat X1/9. Some aspects of the Runabout carried over, such as its 128 underpinnings. The wedge profile, while not as extreme as what was seen on the concept, largely made the cut. Its C-pillar is also reminiscent of the aggressive roll bar. Keen observers might notice some minor additions. Namely, doors, a top, and a full-size front screen. Compromises would have to be made if the car was ever to see the light of day.

Its top is of particular interest in this regard. The American market has always been a critical one for convertibles, but in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, there was a real possibility that they’d be banned outright. To skirt this potential regulation, the X1/9 left the factory with a removable top instead of a fully retractable roof. Although those rules never came to fruition, the setup ended up being for the car’s benefit. It had similar structural rigidity to a closed-body car.

LANCIA STRATOS HF ZERO

Bertone sought to add Lancia to its ever-expanding Rolodex. That automaker usually went to Pininfarina and Zagato for its styling needs and hadn’t yet given Nuccio’s firm a chance. He thought the best course of action would be to show Lancia what they were missing out on. It began working on a car without Lancia’s knowledge. Simply showing the company a concept wouldn’t be enough. Bertone needed to make a statement.

The name early on was Stratolimite, or the limit of the stratosphere. Marcello and his team took this in stride and brainstormed the ways in which they could push the envelope. This philosophy was carried out in terms of the car’s dimensions. The Stratos HF Zero is just 33 inches tall. Not only that, it takes the Carabo’s already dramatic stance even further. Another wheel can fit in the front overhang with plenty of room to spare. The bodywork takes an aggressive angle at the rear wheel and establishes the floor without rounding out.

The main line is absolutely vital to the car. It tapers down the length of the body, which propels the car’s momentum forward and makes it seem as if it’s going downhill. The way the rear kicks up to meet it seals the deal. It makes a perfect arrow, which is just enough to push the body forward. Everything comes second to the pure form, including the headlights. The Zero has neither conventional pop-ups nor Gandini-style light covers. Instead, it uses 10 bulbs arranged in a strip at the very tip of the nose.

This black portion is a stepping pad used to ease entry into the cockpit. Access is granted through the windshield. It flips upward, revealing a set of nearly vertical seats and a faced-up steering wheel. Once the occupants are in place, the driver tilts it into position. Ergonomics are compromised, understandably. The column sits in between the driver’s legs, and the wheel itself comes up well past the knees.

With the design finalized, it was now time for Bertone to present it to their unsuspecting clients. The story goes that Nuccio drove the car to their headquarters and attempted to go into a restricted area. He was denied entry, but rather than turn around, he simply drove under the barrier gate. The guards were probably too dumbstruck to do anything about it. Nuccio was able to get a meeting with Lancia’s bigwigs and convinced them to take the project on. The HF led to the 1973 Stratos, one of the most successful rally cars of all time.

LAMBORGHINI COUNTACH LP500

Lamborghini sought to replace the Miura with a car that employed the lessons learned with the Alfa Romeo Carabo. This was realized in 1971 with the Countach LP 500 prototype. Its silhouette is literally a wedge, arching continuously from the bumper to the rear deck. The front end is somewhat reminiscent of that of the HF Zero. A trio of vents are housed here, and the Countach word mark is also thrown in to keep the design relatively symmetrical. The car has lots of tumblehome. Its greenhouse tapers inward so aggressively that the glass doesn’t have a chance to curve along with it, resulting in windows that are nearly flat. Buttresses are created as the pillars meet the tail lights at their highest point. And you can always count on a Gandini design to have an interesting wheel arch treatment.

Visibility was so abysmal that Bertone needed to “reinvent the wheel,” so to speak. Instead of installing rear-view mirrors, they placed a periscope mirror in the interior. It’s angled toward the driver and is positioned directly in front of an opening on the roof. This didn’t prove to be a very effective solution, as the driver would have to take their eyes off the road to use it. When the production model broke cover in 1974, it had small round mirrors attached to the wings. Other modifications included massive vents on the shoulders, NACA ducts on the body sides, and a more pronounced front bumper.

BMW GARMISCH CONCEPT

Bertone, always eager to forge new relationships with automakers, began working with BMW on the 2200 TI Garmisch show car. Gandini said that the name came from a German ski resort and went on to say that it “evoked dreams of winter sports and alpine elegance.” Most of the cars that we’ve looked at thus far have been at the bleeding edge of design and therefore bore little resemblance to the other models in their respective ranges. With the Garmisch, Bertone aimed for a stronger link between those two worlds. Gandini said that they wanted to stay true to BMW’s design language while sprinkling in a bit of their trademark flair.

The company has used the kidney grille in some form since 1933. Interpretations in the past had been tall, wide, ornate, and everything in between. The Garmisch’s centerpiece is truly one of a kind. They’re vertical, angular hexagons that protrude from the body. Historic models have had either mesh inserts or thin forks as accents. There don’t seem to be any inserts here. This contrasts with the chromed perimeter and gives it more pop.

The profile has traces of the door stops that Bertone had become known for. Take note of the shark nose, beaked hood, angular cabin, and sloping third box. This was a shift from the BMWs of the 60s. The New Class, for instance, had upright screens and a level lower box. Even the tried and true Hofmeister kink had been toyed with. The angle is shallower to keep with the new lines. Above it is a strange grille that shrinks the pillar and retains some of the airiness of older models. The hexagonal screen at the rear adds a bit of depth. In the right conditions, it allows for intriguing interactions between light and shadow.

Bertone’s 911 Roadster seems to have inspired the Garmisch’s interior. Various controls are arranged on a vertical panel near the dashboard. Thankfully, the gauges are behind the steering wheel, where they belong. The high beams, AC, and radio can be adjusted by the driver without them having to take their eyes off the road. Last, but certainly not least, is the glovebox. It pops open like a drawer and even holds a mirror. Passengers could be absolutely certain that they were ready for the occasion.

The Garmisch directly previewed the E12 5-Series and inspired the look of many other BMWs. After its debut at the Geneva Motor Show, it vanished without a trace. Decades later, BMW Design Director Adrian Von Hooydonk found a faded photograph of the car and perused the company’s archives for more information. One might expect to find a wealth of material on such an iconic concept, but he only came away with a few more images. Hooydonk decided to take on the ambitious task of replicating the Garmisch, with Gandini’s permission, of course.

He assembled a small team comprised of members of his design staff as well as a few employees from BMW Classic. Even with this additional manpower and knowledge, there were still many areas that they were unclear on. After all, the team only had a few photographs to work from. To fill these gaps, the company enlisted the help of its creator. Gandini pulled critical details from memory, such as the shade of the champagne metallic paint. The Garmisch recreation made its debut at the 2019 d’Eleganza Villa d’Este. According to Road and Track, Gandini said that he had a hard time distinguishing it from the original. The car is now part of BMW’s classic collection.

MASERATI KHAMSIN

Maserati commissioned Bertone to design a successor to the Ghia and Giugiaro-styled Ghibli. The formula is the same, but the execution is all Gandini. It also points to the changing tastes of the 1970s. Take note of the chiseled character line, flush door handle, and stretched DLO. The theme of asymmetry also continues in the hood vents. A long opening stops as it meets the crease on the right side. It continues higher up near the base of the windshield. Pillar grilles, features that we’ve seen a few times before, are used to extend the greenhouse. The Khamsin’s taillights are affixed to a glass panel. It almost appears as if they’re floating in mid-air. The overall shape of the housing calls back to the Citroen Camargue, another Bertone design. Maserati unveiled the Khamsin on the eve of the oil crisis. Production lasted into 1982, but only 435 examples were built.

NSU TRAPEZE

Bertone created the Trapeze concept car for the ailing NSU brand. According to Audi Club NA, it was shorter than a Lamborghini Urraco while having 4 full-size seats. This packaging was thanks in large part to the placement of its engine. The front seats are set very close together, which frees up additional legroom for the rear seats. A rotary powerplant is nestled in between them. The styling calls back to the production Lancia Stratos, with its wraparound front screen and cab-forward design. Again, the details are what set it apart. Circles seem to be the prevailing theme here. There’s a set on the hood and another pair just behind the window. Even the door handles are nestled inside of roundels. A car like the Trapeze would have surely put NSU back on the map. The damage inflicted by the Ro80 was too much to overcome, though, and the brand soon withered away.

![Trapeze 3'].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6163510905a1267c6e37eabe/1744592183411-1IIHRMLBLOT1W0P9IKQY/Trapeze+3%27%5D.jpg)

LAMBORGHINI BRAVO

Lamborghini had high hopes for the Urraco, its mid-engine 2+2 911 fighter. They expected to sell 2000 a year, but four years in, only a few hundred had been constructed. The automaker then turned its attention toward its successor. Bertone was called upon once again. The Bravo hardly resembled the Urraco P300 that it started out as. Its pillars are smoked and blend in with the glass, creating the most seamless front screen that we’ve seen thus far. The A-pillar crease continues into the sheet metal. Body-colored louvers tie into a similar pattern on the hood. The retractable headlights are disguised somewhat in the process. Those magnesium rotary dial wheels would eventually make their way to the flagship Countach.

Lamborghini had every intention of seeing the Bravo through. The concept wasn’t a foam and plasticine mockup. It was a fully functional prototype that received over 40,000 test miles. Journalists got their hands on it and raved about the driving dynamics. Road and Track even went as far as to say that it was the car the Urraco should have been. Perhaps the Bravo could have been the sales success that Lamborghini was hoping for. The dreaded oil crisis put an end to these ambitions. Ferruccio was forced to sell the company. The new owners had no interest in bringing the Bravo to market. A more focused 2-seater based on the Urraco seemed like a better bet to them. Ironically, the Lamborghini Silhouette would go on to be one of their rarest series production cars. 54 examples were produced between 1976 and 1979, and about 30 are known to exist today. Its successor, the Jalpa, saw greater sales success.

FERRARI RAINBOW

Ferrari, which had a long-standing relationship with Pininfarina, looked to Bertone to style the 308 GT4. The design house sought to strengthen its relationship with the automaker by showing what it could do if it were given a free hand on a concept car. The 308 GT4 Rainbow bears the prancing horse but otherwise hardly resembles your typical Ferrari. This was very intentional. Gandini said:

“I didn’t see much point in designing a Ferrari concept that looked like a Ferrari, as the designers in Pininfarina and others were very much capable of doing so. If we had to do a concept on a Ferrari base, I believed that we needed to look at something that would be radically different than what would be expected.”

Like the Spicup, the Rainbow used a folding roof. Here, it tilts back and goes into a slot just ahead of the roll bar. Road and Track says that this happens in roughly two seconds. The Rainbow seemed to be a bit too adventurous for Ferrari. Bertone would never again style a car for the automaker.

ALFA ROMEO NAVAJO

The coachbuilder used its second 33 Stradale as the basis for the Alfa Romeo Navajo. Its futuristic bodywork is made entirely from fiberglass, contributing to a curb weight of under 2,000 pounds. The headlights don’t pop up out of the hood, but out from the wings. This gives it an unusual, almost alien-like front-end signature. Many of Gandini’s designs have some sort of line that goes across the body perimeter. The Navajo makes use of a thick orange line that gives the silver car a splash of color. More of it can be found on the massive spoiler. The treatment of the wraparound screen is reminiscent of that of the Bravo in the way it motions into the bodywork. It looks even more extreme here and almost makes the Navajo look like a spacecraft out of a 1980s sci-fi flick.

LANCIA SIBLIO

The Lancia Siblio is no doubt the most outlandish and outrageous concept yet. Gandini wanted it to appear as if it were a single piece from a cast. All of the body is a deep bronze color, save for the bright orange strip going across the front of the car. Even the wheels tie into this. They’re made of wood, not metal, and complement the body color. Bertone hand-sprayed the paint on the windows to achieve a gradient effect. Much of it doesn’t move. The only part that does is this porthole near the end of the door. The doors themselves are made of plexiglass. Apparently, their glass supplier failed to meet the deadline, so Bertone had to improvise with these in order to meet their deadline.

CITROEN BX SAGA

In 1977, Bertone collaborated with Reliant on the FW11 project. It was a 4-door lift back with a tall cabin and large windows. According to Carrozzieri Italiani, it was originally envisioned as a successor to the Turkish Anadol. Reliant was also considering it as a replacement for its Scimitar. Four prototypes were constructed before the project was canceled.

Traces of the FW11 would show up in the XJS-based Jaguar Ascot concept. The fascia is also similar to that of the Ferrari Rainbow, with the wide grille, asymmetrical logo, and trick headlights. It also carries over that car’s trapezoidal front wheel well. The rear well, meanwhile, is an amped-up version of the Reliants. Jaguar passed on this car.

Gandini took the opportunity to develop the design further in 1979 when Bertone received a brief from Volvo. According to an article from Top Gear, it was assigned to restyle the homely 343 hatchback. Compared to the rest of the company’s range, the Tundra may as well have been from another planet. Volvo’s corporate grille is low and off-center. The A and C-pillars are darkened, giving the impression of a floating roof. Compared to the FW11 and Ascot, the Tundra reeled in the overall dimensions and opted for softer surfacing. It seemed like the shot in the arm that the brand was looking for, but Volvo rejected it. It was far from dead, though. It finally saw the light of day in 1982 in the form of the Citroen BX.

The front end has a bit in common with the Tundra. The grille is on the lower part of this section, leaving the headlights, turn indicators, and offset badge as the only elements up top. The wheel arch treatment is similar as well, with the main body line going through the front ones and above the rear ones. The ones in the back have a pinch of Gandini’s flair. It covers a bit of it and swoops upward. It diverges from the others a bit more around the back. It enlarges the greenhouse by darkening a chunk of the C-pillar and uses two square lights to visually widen the car.

The BX is by far Gandini’s most successful model. It was offered from 1982 to 1993, and in that span, Citroen sold over 2 million of them. The man himself would be long gone by the time it actually came to market. The Mazda Cosmo, Luce, and 929 were the final cars done under his guidance. After more than 15 years at Bertone, Gandini stepped down as chief of design and went freelance.

LAMBORGHINI DIABLO/CIZETA V16T

There was no shortage of work. Lamborghini looked his way for a proposal for a Countach replacement. The car, known internally as the P132, was very much an evolution of what it was set to succeed. Angular styling and massive shoulder vents transfer over to the new model. Unlike the Countach, the P132 is a clear two-box design. The canopy takes on a teardrop shape as it tapers toward the deck, emphasizing the hips and hinting at the immense power of the engine. Partway through development, the company fell under the control of Chrysler. The harsh lines were ironed out over subsequent design studies, and the 1990 Diablo was a suave thing in comparison.

Soon after leaving the P132 project, Gandini was invited to submit a proposal for the Cizeta-Morodor V16T. Classic Driver states that his original design for the Diablo was used as the basis for the car. There are some links between the two models, such as the lightning elements on the lower clip, the pop-up location, and the sloping window line. There are also some differences. Take these buttresses, for instance. On the prototype, they stretch all the way back to the deck. The louvers continue up past these, creating geometric pillars that call back to the features from cars like the Marzal and Garmisch. This wasn’t quite to the tastes of company head Claudio Zampolli. The production car combined elements and ideas from all of those cars.

MASERATI CHUBASCO

Yet another supercar was on the docket for Gandini. After years of prioritizing sales volume, Maserati began developing a true halo car. At its end-of-year press conference in December 1990, the company unveiled the Chubasco. It was a mockup and therefore didn’t actually run. Still, those in attendance probably thought the future looked bright for the brand. The Chubasco’s time in the sun was brief. Fiat acquired a 50 percent stake in Maserati in 1990, and the project was canceled not long after.

STOLA S81

In 2001, Stola presented him with the opportunity to revisit one of his most iconic designs. The company was known for, among other things, its expertise in prototyping. It wanted to show the advantages of its newly developed epoxy resin, which it claimed was superior to standard modeling clay. The Stratos-inspired Stola S81 was intended to do just that. Lancia still had the rights to the name. S81 signified the 81st birthday of company founder Alfredo Stola. While the car has an eye toward the past, it does more than enough to stand on its own. Bright, compact LEDs gave Gandini more freedom to experiment with the lighting units. The upper portion illuminates the road ahead, while the lower part serves as the turn indicator. The body cuts into them, creating a dynamic front-end signature.

The Stratos’ wraparound screen makes the transition to the S81. Due to the heavily raked windshield and massive shoulder vent, the window has to take an extreme angle up. This gives the car an aggressively pinched greenhouse that makes it feel larger than it actually is. The plan view does look pretty neat, though. Around back, a continuous LED strip highlights the surfacing of the deck.

STOLA S86 DIAMANTE

Gandini and Stola collaborated again in 2005 on the S86 Diamante. The company wanted to show prospective clients that it was capable of turning out work under strict deadlines. Development took just over five weeks, and it really shows in the uninspired styling. The S86 also has the worst rear wheel well yet. It looks like a complete afterthought.

TATA RACEMO

Gandini was also involved in the development of the 2017 Tamo RaceMo concept. It was pitched as a low-cost sports car geared toward the Indian market. Tata Motors canceled the project due to financial issues. It felt that the resources the car would have needed to bring to market would have been better put toward their commercial vehicle endeavors.

DEATH

Marcello Gandini passed away on March 13, 2024, at the age of 85. The legendary designer was survived by his wife, two kids, and three grandchildren. He also left behind a legacy matched by few in automotive history. After dropping out of school, he carved his own path into the industry and earned a position at Bertone. The firm didn’t skip a beat in the transition from Giugiaro to Gandini. Some of the most iconic cars of all time were created while he was at the helm. Family sedans, T-top sportsters, poster-worthy coupes, and everything in between came out of the coachbuilder during this time. He continued to make an impact as a freelancer, reimagining some of his most iconic designs and creating a few new ones. Marcello Gandini was one of the greatest car designers of all time and is definitely an industry Icon!